Shanghai architecture Expo: an empty experience?

Thomas Heatherwick’s much-hyped design for the British pavilion may be beautiful, but it lacks the crowd-pleasing magic of the great exhibitions age

-

-

- guardian.co.uk,

Wednesday 5 May 2010 16.37 BST

- Article history

- guardian.co.uk,

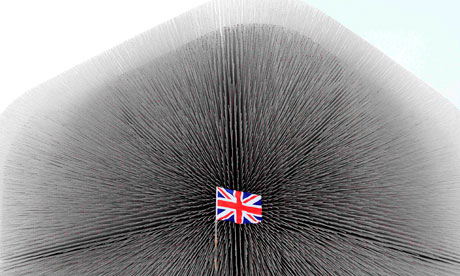

An alluring nothing? The Seed Cathedral, Thomas Heatherwick’s pavilion for the Shanghai Expo 2010. Photograph: Aly Song/Reuters

The hype surrounding the British pavilion at the Shanghai Expo has been so great that it’s little surprise that some people have come away disappointed. After queuing for up to five hours in the blazing heat, all expectant Chinese visitors have discovered inside the prickly pavilion is … well, nothing. No enticing British exhibits, no music, no welcome drinks and snacks, not even a film, much less a presentation showing the best of British design and innovation, or all the zillions of things the British buy from the Chinese. Perhaps there should have been a warning sign outside.

While its design is certainly exciting, the pavilion is not meant to display anything other than itself. Designed by the much-feted Thomas Heatherwick, this spiky cube is a kind of giant, stylised dandelion at the point where the seeds are about to fly off. Each of Heatherwick’s 60,000 perspex prickles contains a seed from Kew Gardens’ Millennium Seed Bank in Wakehurst, West Sussex. The plan is apparently for the prickles and their seeds to be donated to schools across China when the £35bn expo closes its gates at the end of the year. Although the prickles channel tiny shafts of daylight inside the British pavilion, there is nothing else here to see.

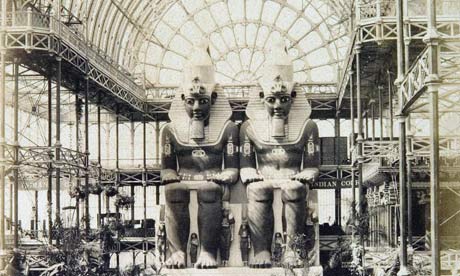

Revolutionary … Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, which housed the Great Exhibition of 1851. Photograph: Philip Henry Delamotte/Dominic Winter Auctions/PA

Revolutionary … Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, which housed the Great Exhibition of 1851. Photograph: Philip Henry Delamotte/Dominic Winter Auctions/PA

The concept is endearing, yet expos are as much about popular entertainment as they are to do with philosophy or subliminal experiences. This doesn’t mean they have to be banal. They do, though, need to engage the imagination of enormous, queuing crowds. Perhaps the problem is that, like so many expos of the past two decades, architectural pavilions have become self-referential artworks. This might be fine in an art show, but not, perhaps, here.

The very first world expo – the Great Exhibition of 1851 – offered a mind-blowing building, Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, that happened to be filled to its iron and glass gunwhales with all sorts of things from gothic revival cabinets to the latest machinery via high Victorian kitsch. Offering a comprehensive snapshot of mid-century British commercial culture, the building itself was truly revolutionary. Another famous expo, that in Paris in 1889, featured an equally breathtaking building, the vast Machine Hall, designed by the architect Charles Dutert and the engineer Victor Contamin, which was chock-full of the very latest technological wonders. Mobile platforms, guided by rails, took 100,000 visitors a day on a journey above the machines that would shape the following century.

Decades later, even such determinedly experimental and “artistic” expo pavilions as the one Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis designed for Philips at Brussels in 1958, offered magical experiences once inside. An “Electronic Poem”, a kind of hyper-sophisticated son-et-lumière, animated the interior of this unexpected hyperbolic-paraboloid concrete tent. If challenging, the experience had been worth queuing up for.

Expos are not art shows. And in a stiflingly hot and humid city such as Shanghai you need to offer visitors something a little more, in fact a lot more, than even the most alluring nothing.